Hepatitis D is an inflammation of the liver caused by the hepatitis D virus (HDV), which only infects those living with hepatitis B virus (HBV).1

Overview of Hepatitis D

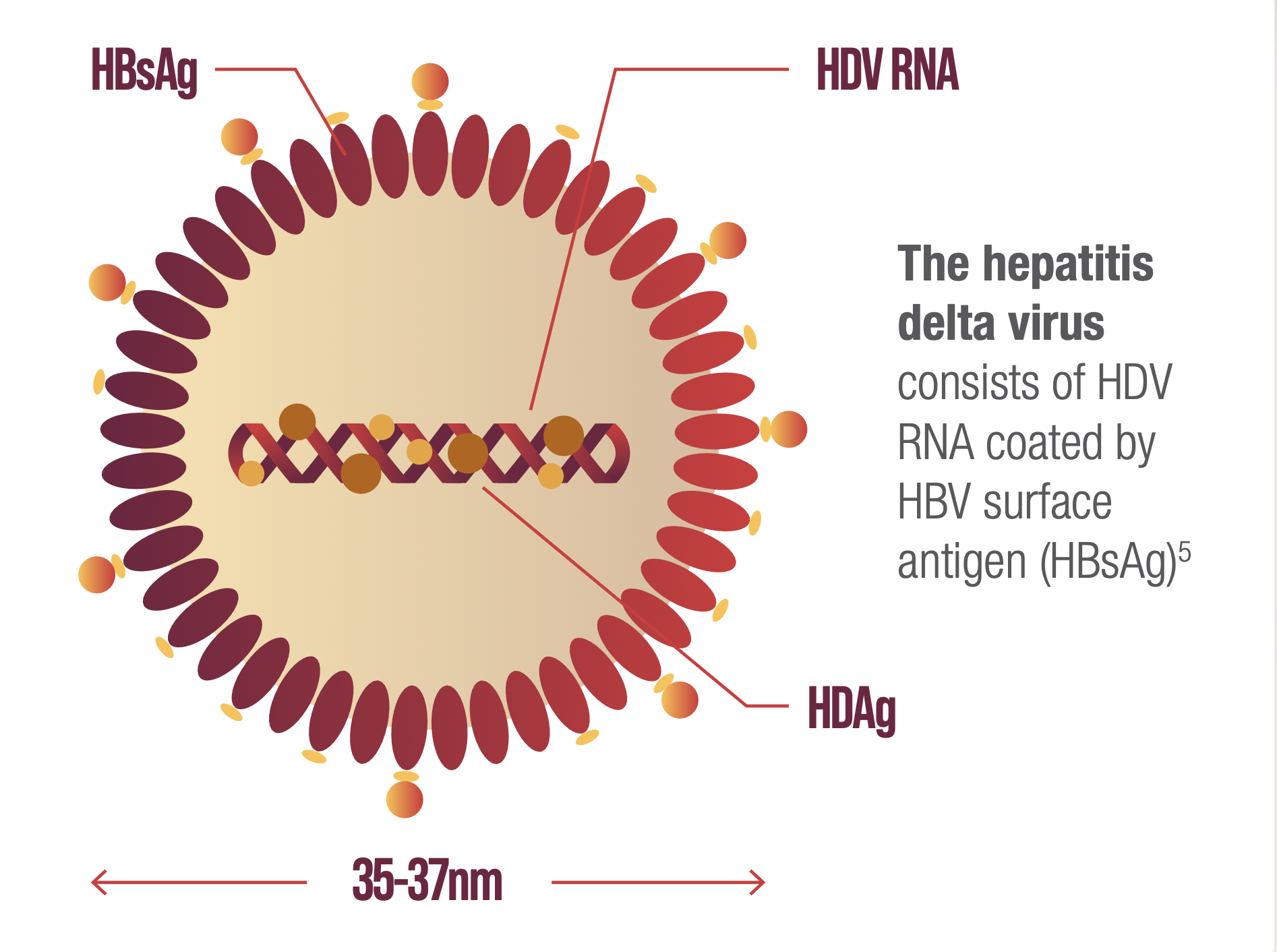

HDV structure and the role of HBV in its lifecycle

HDV requires the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) to form HDV virions enabling de novo entry into hepatocytes and dissemination of infection.2,3

Once inside the liver cell, the hepatitis delta virus genome (1.7 kb) is too small to encode an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and relies on the host machinery to replicate.2–4

THE HEPATITIS DELTA VIRION

HDV transmission can occur through several routes6,7

HDV prevalence and epidemiology

HDV affects millions of people around the globe and its prevalence is likely underestimated.8–10

It is estimated that HDV affects between 4.5% and 13% of HBsAg-positive patients.11,12

In the UK, the prevalence of HDV is estimated to be between 2.1% and 9.9%.13,14

Current available data suggests that HDV is most prevalent in Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Central Latin America, and West and Central Africa.11

There are several factors that contribute to the lack of accurate estimates:8–10

- No universal HDV screening of HBsAg-positive individuals

- Lack of accuracy and standardised confirmatory tests

- Variable estimates from individual countries

- HBV prevalence underestimated and lack of HBV central UK registry.

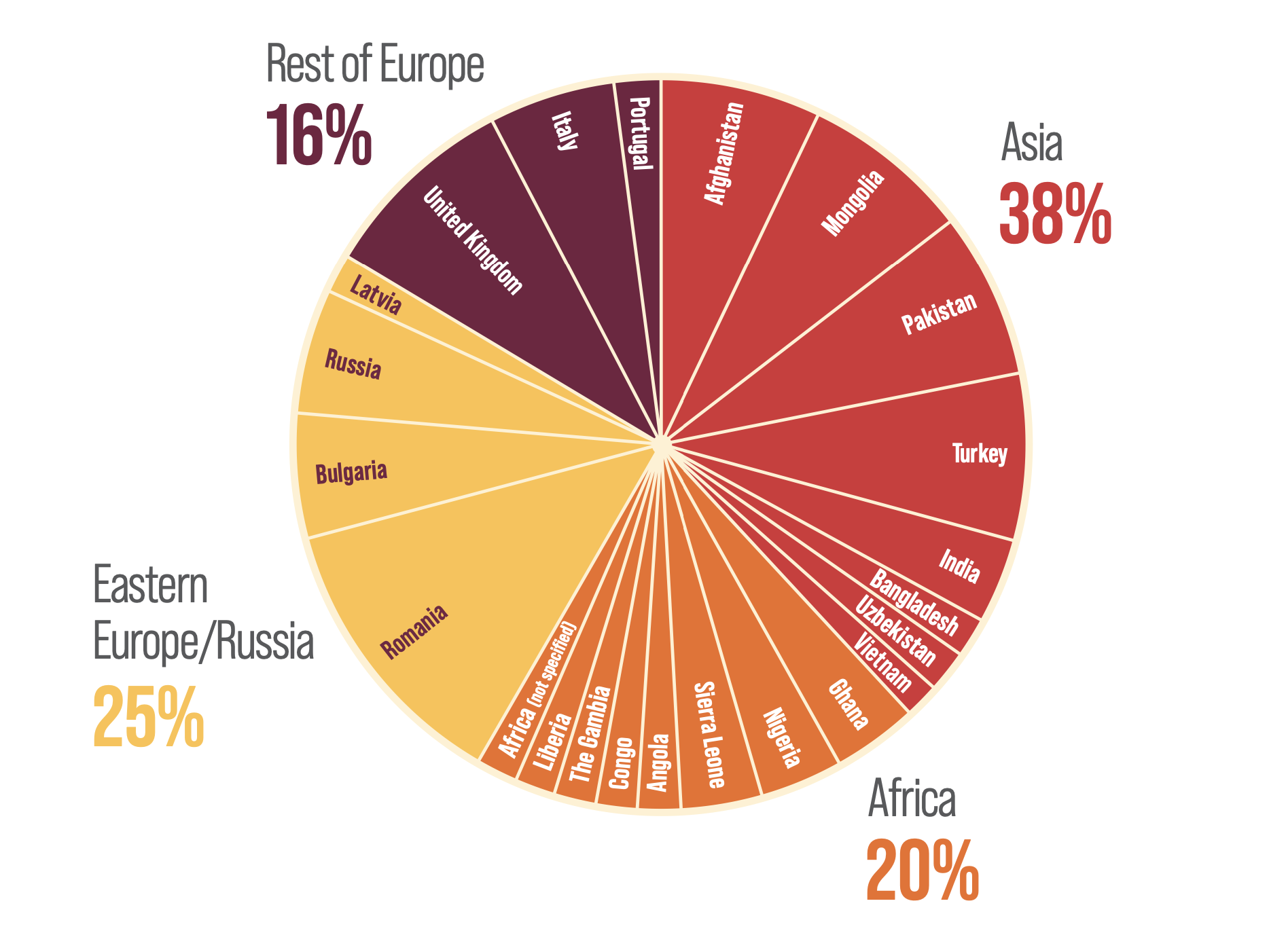

Data suggest that HDV patients in the UK typically originate from other countries15,16

Nearly all patients with active HDV infection identified in London had immigrated to the UK.15

- A cross-sectional study of HDV screening rates in HBV patients attending 4 London hospitals from January 2005 to June 2012a found that between 4.5% (n=158/3543) and 6% (n=4/67) of patients were seropositive for HDVb, with 91% (n=50/55) of patients with active HDV infectionc originating from outside the UK.15

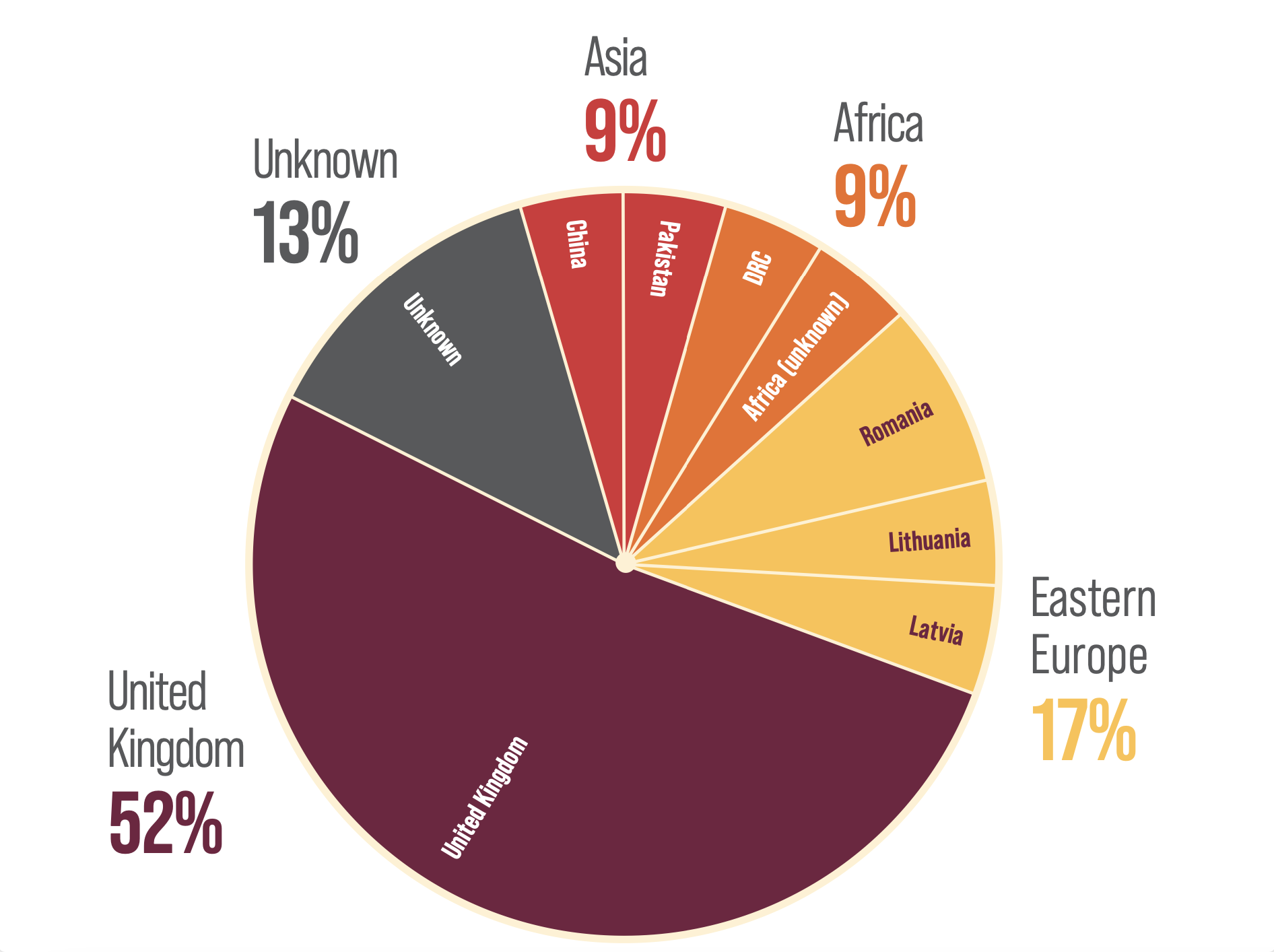

1 in 3 HDV patients in West Scotland originated from outside the UK.16

- An observational study of HDV prevalence in patients in West Scotland diagnosed with HBV under the care of the Greater Glasgow and Clyde health board and the NHS Lanarkshire health board, found that, between April 2011 and May 2016, the calculated HDV seroprevalence was 1.6% (n=16/991) and 4.9% (n=7/142) respectively.16

REGION OF ORIGIN OF PATIENTS WITH ACTIVE HDV INFECTION IN LONDON (N=55)15,c

Figure drawn from El Bouzidi K, et al. 201515

REGION OF ORIGIN OF HDV-INFECTED PATIENTS IN WEST SCOTLAND (N=23)16

Figure drawn from Jackson C, et al. 201816

aTwo centres used clinic-led testing but there were insufficient data to determine the rate of testing.

bCentre 1: HDV testing performed over a 3-month period (June 2012–August 2012) in HBV patients (n=168) attending the centre clinics. HDV seroprevalence was 6% (n=4/67) and the screening rate was 40% (n=67/168). Centre 2: Reflex-led anti-HDV testing of all first HBsAg positive samples performed between 2001 and 2012. HDV seroprevalence was 4.5% (n=158/3543) and screening rate was 99.4% (n=3543/3563). Comparisons should not be made between centres due to differences in populations. Centre 3 and Centre 4, used clinic-led testing but there were insufficient data to determine the rate of testing.

cActive HDV infection was defined by detectable HDV RNA.

dHDV genotype was not known in all the patients presented within this figure.

Chronic HDV infection: Morbidity and mortality

Chronic HDV infection has the highest mortality rate of any viral hepatitis.17

Patients with chronic HDV infection experience rapid progression towards liver failure.17 In addition, compared to individuals living with HBV alone, patients also infected with HDV are at a higher risk of developing more severe liver disease, including:8,17–19

- 3-6x more likely to develop liver cancer

- 2-3x more likely to develop cirrhosis.

As HDV only infects those living with HBV,1 it is important to focus screening efforts of HDV on all patients with HBV.

HDV management: Therapeutic challenges

The goal of HDV treatment is to suppress HDV replication, which is usually associated with the normalisation of liver enzymes.20

Nucleos(t)ide analogue treatments for HBV are not effective against HDV,20,21 but achieving HDV treatment goals aims to prevent long-term complications of HDV infection, including:5

- Cirrhosis

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Liver transplantation

- Liver-related death.

HDV screening

HDV screening and testing rates are low,15,22 but because of the severity of chronic HDV infection,8,17 screening is urgently needed.11

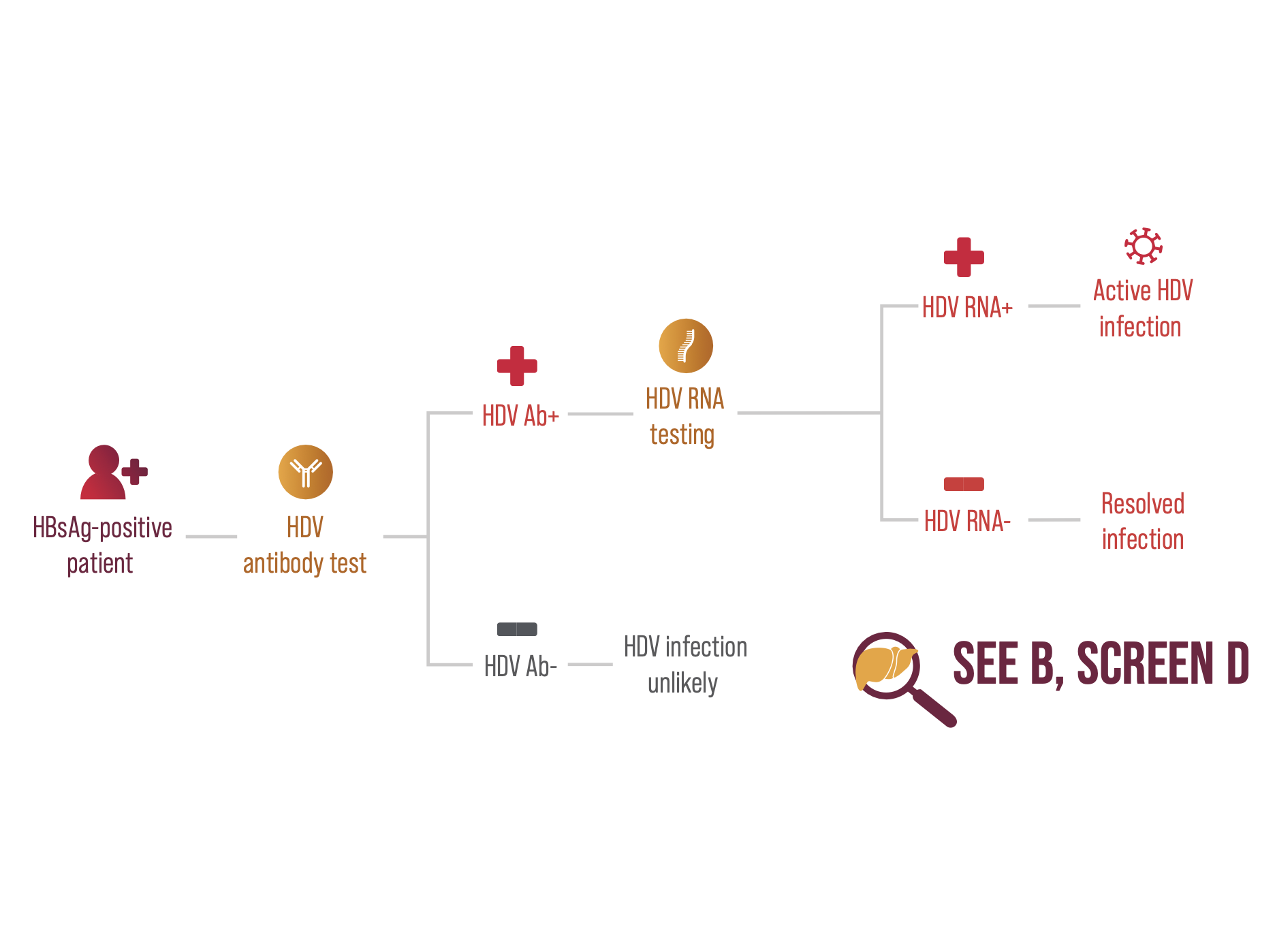

Screening HBsAg-positive individuals for HDV diagnosis involves 2 steps:8,23

- Start with an HDV antibody test

- If positive, confirm with a HDV RNA test.

Guidelines

Screening HBsAg positive individuals for HDV helps facilitate the next steps in HDV management.24,25

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommends HDV screening for all HBsAg-positive patients and re-testing for anti-HDV antibodies in HBsAg-positive individuals whenever clinically indicated; re-testing may be performed yearly in those remaining at risk of infection.26

NICE recommend HDV screening in primary care for all HBsAg-positive patients.27

Abbreviations:

Ab = antibody; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV = hepatitis B virus; HDAg = hepatitis D antigen; HDV = hepatitis D virus; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; RNA = ribonucleic acid.

UKI-HPX-0037

Date of preparation April 2025